Vector-borne disease: Ehrlichia spp. infection

Canine Ehrlichiosis

Andy Pachikerl, Ph.D

Introduction

Ehrlichiosis is a disease of dogs, humans, livestock, and wildlife that is widely distributed around the world and is transmitted by tick vectors. The pathogen of the disease, Ehrlichia, was renamed and classified in 2001 according to the bacterial 16S RNA and groESL gene nucleic acid sequences, and is classified as Rickettsiales, Anaplasmataceae, Ehrlichia genus of bacteria (Allison and Little, 2013).) With global warming, the expansion of tick habitats and the prevalence of cross-border tourism, the chances of the disease spreading to non-endemic areas have increased.

How is a dog infected with Ehrlichia?

Ehrlichiosis is a disease that develops in dogs after being bitten by an infected tick. In the United States, E. canis is considered endemic in the southeastern and southwestern states, though the brown dog tick is found throughout the United States and Canada.

(Photo credit: https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/ehrlichiosis-in-dogs)

Pathogens and transmission.

Ehrlichia spp. are gram-negative, small, obligatory intracellular bacteria. There are currently three types of Ehrlichia spp.: not limited to dogs: Elyse infection, dogs as hosts: E. canis, E. chaffeensis, and E. ewingii.

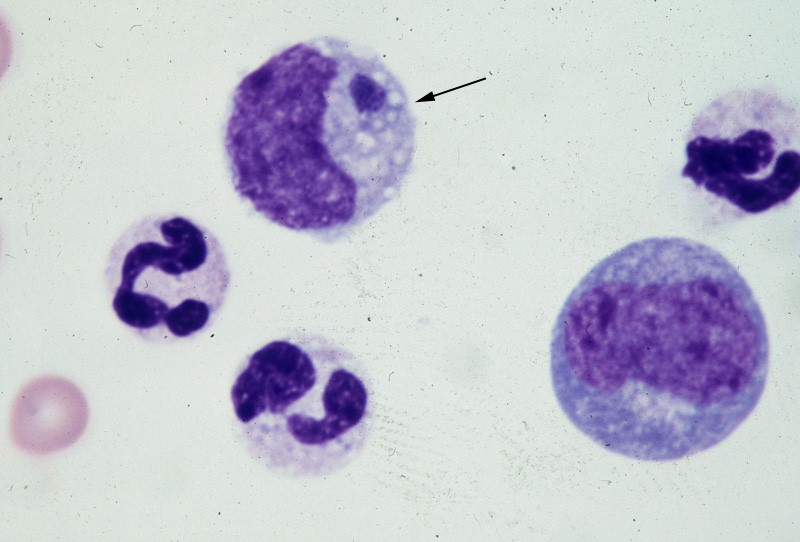

E. canis can infect dogs causing monocytic ehrlichsis (canine monocytic ehrlichsis, CME). Cells most commonly infected by E. canis are monocytes and lymphocytes (Figure 1). CME occurs mainly in tropical and subtropical regions, but there are also cases of infection in other regions. E. chaffeensis infects single-core balls of dogs and humans, mainly in North America, South America, Asia and Africa. E. ewingii is a zoonotic infectious disease that infects particulate white blood cells and is found mainly in North America, South America and Cameroon, Africa. E. ewingii causes human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (Bulleretal., 1999). E. chaffeensis infects humans known as human monocytic ehrlichiosis. E. canis also causes human infections (Maeda et al., 1987).

Ehrlichia spp. life history is that of vector ticks and mammalian hosts. After sucking the blood of infected animals, the larvae transmit the disease to the new host via saliva when they bite and suck the blood of other animals. E. canis, E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii have been shown to mediate life cycle transmission in an intermediary hosts that are usually arthropods. This have shown to stabilize its life cycle transmission, which is also known as Transstadial transmission in arthropods, and blood transfusions or bone marrow may also cause the spread of the disease. The main vector arthropods in E. canis are Rhipicephalus sanguineus and Dermacenter variabilis even though the main host are canines including domestic dogs. Other canine family it can infect are wolves, coyotes, and foxes. The other species, E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii consist of hosts from the arthropod family such as Amblyomma americanum, a main vector and other arthropods such as Haemaphysalis, Dermacentor, and Ixodes. E. chaffeensis usually infects white-tailed deer, and E. ewingii to hosts that are likely deer and dogs.

Figure 1. Ehrlichia canis in the monocyte (arrow) (Wright’s stain, 1000x)

Figure 1. Ehrlichia canis in the monocyte (arrow) (Wright’s stain, 1000x)

(Source: http://www.eclinpath.com/ngg_tag/infectious-agent/nggallery/page/9)

Clinical symptoms.

The clinical symptoms and severity of Ehrlichiosis depend on the type of Elysian infection and the host’s immune response. The course of E. canis infection in dogs can be divided into acute, subclinical and chronic, but in naturally infected dogs it is not easy to distinguish between these three stages. If there is a co-infection with other pathogens, it will also aggravate the severity of the disease.

The acute period lasts about three to five weeks and can cause fever, poor spirits, loss of appetite, swollen lymph nodes and swollen spleen. Increased eye secretions, pale mucosa, bleeding disorders (bleeding spots, or runny nosebleeds), or neurological symptoms caused by meningitis. Vomiting, diarrhea, lameness, reluctance to walk, stiff pace, and leg or scrotum edema. The most easily observed hematological abnormalities are white blood cell reduction, platelet reduction, and anemia. When clinical symptoms disappear, they are often accompanied by subclinical periods that last for several years (Waner et al., 1997). Although some cases can be fatal, others heal on their own. When a dog is unable to clear the pathogen of infection, the course of the disease develops into a subclinical persistent infection to become a primary dog. Some infected dogs enter a chronic period. During the chronic period, symptoms and hematological abnormalities, including platelet reduction, anemia and total blood cell reduction, all relapse and become more severe than it was during acute periods. When the severity maximizes in a few cases, the dogs will not respond to antibiotic treatment and ceased to heal, and eventually they die from heavy bleeding, severe weakness, or secondary pathogenic infections.

Many times, when an infected dog that has contracted E. chaffeensis, the diagnoses points out to other pathogens since there are little information as to E.chaffeensis and dog infections also, the clinical symptoms are similar to that of infection with E. canis. Symptoms include easy bleeding (bleeding spots, blood urine or nosebleeds), vomiting, and swollen lymph nodes. The most common symptom of infection with E. ewingii is fever. Other symptoms include lameness, multiple arthritis, terminal edema, swollen lymph nodes, reduced platelets and anemia, some of which can cause neurological symptoms in dogs.

Diagnosis.

Ehrlichiosis can be diagnosed by microscopy, serology, or PCR. Diagnosis is complicated when other arthropod-mediated pathogens are used.

Blood smears have been observed to infect blood cells to help diagnose the disease. However, this method is time-consuming and can only be observed in a small number of cases during acute infection, so it is not a reliable diagnostic method.

Serological examinations are often used to assess Ehrlichiosis. Detection of IgG antibody deposits indicated that dogs had been exposed to pathogens, and two serological examinations two weeks apart during the acute period showed an increase in antibody force prices. Caution should be exercised when a single test result is judged, as healthy dogs may also be antibody positive. Antibodies cannot be detected in the early stages of infection. Additionally, antibodies produced during and after an infection with E.canis, E. chaffeensis, or E. ewingii can also have a cross reaction with each other and it can lead to a disruption of the diagnosis that can distinguish original cause of infection. (Cardenas et al., 2007).

With the use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) diagnosis for E.canis can turn out to be the most reliable due to its high sensitivity as well as specificity to detect pathogen’s genes encoding for antibodies produced at a very early stage of infection the dog has for E. canis (earlier than using immunochromatography labeling using peptides) 4-10 days after infection (Harrus et al., 2004). PCR testing can be applied to whole blood, bone marrow or spleen samples. Another advantage of PCR testing is that it can confirm which pathogens are causing the infection.

Treatment.

Dogs experiencing severe anemia or bleeding problems may require a blood transfusion. However, this does nothing to treat the underlying disease.

Certain antibiotics, such as doxycycline, are quite effective. A long course of treatment, generally four weeks, is needed. This is the treatment of choice as it is easily accessible and generally well tolerated. Alternatively, imidocarb (not available in Canada) can be used intravenously. Your veterinarian will discuss treatment options with you as some supportive medications such as steroids may be needed depending on the clinical state of the patient and blood parameters.

(Phot credit: https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/ehrlichiosis-in-dogs)

(Phot credit: https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/ehrlichiosis-in-dogs)

Anilsa (22mg/kg every 8 hours) or doxycyclin (5 mg/kg every 12 hours) were given for 4 weeks. Most acute or subclinical periods are curable after treatment with the right amount of antibiotics (Harrus et al., 2004). In severe cases, supportive therapy such as blood transfusions or infusions should be given at the same time. Poor prognosis is usually expected when the course of disease enters the chronic period of the disease (Mylonakis., 2004). Cokeworms or Partocycal bacteria also often cause death during chronic infection.

Periods up to a year may be necessary for complete hematological recovery. The long-term prognosis following treatment is much more variable, potentially related to failure to diagnose concurrent infections. Undiagnosed infection with a Babesia spp. or Bartonella spp. can be misinterpreted as an ineffective therapeutic response when treating ehrlichiosis, as doxycycline is generally an ineffective treatment for babesiosis and bartonellosis. Experimentally, enrofloxacin will suppress the clinical manifestations of E. canis infection and may result in hematological improvement but does not eliminate the infection. Although imidocarb dipropionate has gained clinical acceptance in some endemic regions for treating severe or refractory cases of ehrlichiosis, lack of efficacy has been demonstrated in both naturally and experimentally infected dogs. Dogs co-infected with other tick-borne pathogens, may respond over a longer period of weeks or relapse following doxycycline treatment. Animals are not resistant to re-infection following successful clearance of bacteria, therefore the use of safe and effective acaracide products are critical to help prevent re-infection.

Prevention and control.

There is currently no vaccine to prevent infection with the disease. The best way to prevent it is to reduce the chances of animals contacting arthropods. Wearing anti-hard collars or oral anti-hardening drugs on animals can also help.

Can humans get ehrlichiosis from infected dogs?

No. However, humans can get canine ehrlichiosis from tick bites. The disease is only transmitted through the bites of ticks. Therefore, even though the disease is not transmitted directly from dogs to humans, infected dogs serve as sentinels, or warnings to indicate the presence of infected ticks in the area.

References

- Allison RW, Little SE. 2013. Diagnosis of Rickettsial diseases in dogs and cats. Vet Clin Pathol. Jun;42 (2):127-44.

- Buller RS, Arens M, Hmiel SP, Paddock CD, Sumner JW, Rikhisa Y, Unver A, Gaudreault-Keener M, Manian FA, Liddell AM, Schmulewitz N, Storch GA. 1999. Ehrlichia ewingii, a newly recognized agent of human ehrlichiosis. N Engl J Med. ; 341(3):148-55.

- Cardenas AM, Doyle CK, Zhang X, Nethery K, Corstvet RE, Walker DH, McBride JW. 2007. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with conserved immunoreactive glycoproteins gp36 and gp19 hass enhanced specty and provides species-immunodiagnosis of Ehrlichia. canis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 14(2):123-8.

- Harrus S, Kenny M, Miara L, Aizenberg I, Waner T, Shaw S. 2004. The Same of the state of the splenic sample PCR with blood sample PCR for the diagnosis and treatment of the emerable Ehrlichia canis information. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 48(11):4488-90.

- Kimberley Dog Controlled Area – dog movement conditions. Government of Western Australia, Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Agriculture and Food division. June 4, 2020. Retrieved June 4, 2020.

- Little, Susan E. 2010. Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis in Dogs and Cats. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 40 (6): 1121–40.

- Maeda K, Markowitz N, Hawley RC, Ristic M, Cox D, McDade JE. 1987. Humanis with Ehrlichia canis, a leukocytic rickettsia. N Engl J Med. 316 (14): 853-6.

- Mylonakis ME, Koutinas AF, Breitschwerdt EB, Hegarty BC, Billinis CD, Leontides LS, Kontos VS. 2004. Chronic canine ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia canis): a retrospective study of 19 natural cases. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 40 (3): 174-84.

- Perez, M.; Bodor, M.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, Q.; Rikihisa, Y. 2006. Human Infection with Ehrlichia Canis Accompanied by Clinical Signs in Venezuela. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1078: 110–7. doi:10.1196/annals.1374.016.

- Waner T, Harrus S, Bark H, Bogin E, Avidar Y, Keysary A. 1997. Characterization of the subclinical phase of the canine ehrlichiosis in the emly infected beagle dogs. Vet Parasitol.69 (3-4): 307-17.