Andy Pachikerl, Ph.D

Introduction

Pancreatitis appears to be a common disease in cats,1 yet it remains frustratingly difficult to establish a clinical diagnosis with certainty. Clinicians must rely on a combination of compatible clinical findings, serum feline pancreatic lipase (fPL) measurement, and ultrasonographic changes in the pancreas to make an antemortem diagnosis, yet each of these 3 components has limitations.

Acute Versus Chronic Pancreatitis

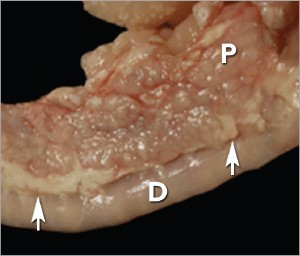

Acute pancreatitis is characterized by neutrophilic inflammation, with variable amounts of pancreatic acinar cell and peripancreatic fat necrosis (Figure 1).1 Evidence is mounting that chronic pancreatitis is more common than the acute form, but sonographic and other clinical findings overlap considerably between the 2 forms of disease.1-3

Diagnostic Challenges

Use of histopathology as the gold standard for diagnosis has recently been questioned because of the potential for histologic ambiguity.3,4 A seminal paper exploring the prevalence and distribution of feline pancreatic pathologic abnormalities reported that 45% of cats that were apparently healthy at time of death had histologic evidence of pancreatitis.1 The 41 cats in this group included cats with no history of disease that died of trauma, and cats from clinical studies that did not undergo any treatment (control animals). Conversely, multifocal distribution of inflammatory lesions was common in this study, raising the concern that lesions could be missed on biopsy or even necropsy.

Prevalence

Such considerations help explain the wide range in the reported prevalence of feline pancreatitis, from 0.6% to 67%.3 The prevalence of clinically relevant pancreatitis undoubtedly lies somewhere in between, with acute and chronic pancreatitis suggested to represent opposite points on a disease continuum.2

FIGURE 1. Duodenum (D) and duodenal limb of the pancreas (P) in a cat with acute pancreatitis and necrosis; well-demarcated areas of necrosis are present at the periphery of the pancreas in the peripancreatic adipose tissue(arrows). Courtesy Dr. Arno Wuenschmann, Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory

Risk factors

No age, sex, or breed predisposition has been recognized in cats with acute pancreatitis, and no relationship has been established with body condition score.3-5

- Cats over a wide age range, from kittens to geriatric cats, are affected; cats older than 7 years predominate.

- In most cases, an underlying cause or instigating event cannot be determined, leading to classification as idiopathic.3

- Abdominal trauma, sometimes from high-rise syndrome, is an uncommon cause that is readily identified from the history.6

- The pancreas is sensitive to hypotension and ischemia; every effort must be taken to avoid hypotensive episodes under anesthesia.

Comorbidities

In cats with acute pancreatitis, the frequency of concurrent diseases is as high as 83% (Table 1).2

- Pancreatitis complicates the management of some diabetic cats and may induce, for example, diabetic ketoacidosis.7

- Anorexia attributable to pancreatitis can be the precipitating cause of hepatic lipidosis.8

- The role of intercurrent inflammation in the biliary tract or intestine (also called triaditis) in the pathogenesis of pancreatitis is still uncertain.

Roles of Bacteria

In one study, culture-independent methods to identify bacteria in sections of the pancreas from cats with pancreatitis detected bacteria in 35% of cases.9 This report renewed speculation about the role of bacteria in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis, and the potential role that the common insertion of the pancreatic duct and common bile duct into the duodenal papilla may play in facilitating reflux of enteric bacteria into the “common channel” in cats. Awareness of triaditis may affect the diagnostic evaluation of individual patients.

Table 1. Clinical Data from 95 Cats with Acute Pancreatitis (1976—1998; 59% Mortality Rate) & 89 Cats Diagnosed with Acute Pancreatitis (2004—2011; 16% Mortality Rate)

| PARAMETER | HISTORICAL DATA* | CATS WITH PANCREATITIS† | SURVIVING CATS WITH PANCREATITIS† |

| Number of Cats | 95 | 89 | 75 |

| ALP elevation | 50% | 23% | 18% |

| ALT elevation | 68% | 41% | 36% |

| Apparent abdominal pain | 25% | 30% | 32% |

| Cholangitis | NA | 12% | 11% |

| Concurrent disease diagnosed | NA | 69% | 68% |

| Dehydration | 92% | 37% | 42% |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | NA | 8% | 5% |

| Diabetes mellitus | NA | 11% | 12% |

| Fever | 7%‡ | 26% | 11% |

| GGT elevation | NA | 21% | 18% |

| Hepatic lipidosis | NA | 20% | 19% |

| Hyperbilirubinemia | 64% | 45% | 53% |

| Icterus | 64% | 6% | 6% |

| Vomiting | 35%—52% | 35% | 36% |

| ALP = alkaline phosphatase; ALT = alanine aminotransferase; GGT = gamma glutamyl transferase; NA = not available | |||

| * Summarized from 4 published case series; a total of 56 cats had acute pancreatitis diagnosed at necropsy and 3 by pancreatic biopsy5,8,10,11 † Data obtained from reference12 ‡ 68% of cats were hypothermic |

|||

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Many cats with pancreatitis have vague, nonspecific clinical signs, which make diagnosis challenging.5 Clinical signs related to common comorbidities, such as anorexia, lethargy, and vomiting, may overlap with, or initially mask, the signs associated with pancreatic disease.

Early publications on the clinical characteristics of acute pancreatitis required necropsy as an inclusion criterion, presumably skewing the spectrum of severity of the reported cases.5,8,10,11 Cats with chronic pancreatitis were excluded from these reports.

Clinical Findings

Table 1 lists common clinical findings in cats from necropsy-based reports and a recent series of 89 cats with acute pancreatitis studied by the authors.12

- Note the lower prevalence of most clinical findings in the cats diagnosed clinically rather than from necropsy records.

- In our evaluation of affected cats, 17% exhibited no signs aside from lethargy and 62% were anorexic.

- Vomiting occurs inconsistently (35%—52% of cats).

- Abdominal pain is detected in a minority of cases even when the index of suspicion of pancreatitis is high.

- About ¼ of cats with pancreatitis have a palpable abdominal mass that may be misdiagnosed as a lesion of another intra-abdominal structure.

Laboratory Analyses

Hematologic abnormalities in cats with acute pancreatitis are nonspecific; findings may include nonregenerative anemia, hemoconcentration, leukocytosis, or leukopenia.

Serum biochemical profile results vary (Table 1). In our acute pancreatitis case series, 33% of cats had no abnormalities in their chemistry results at presentation.12

Serum cholesterol concentrations may be high in up to 72% of cases. Some cases of acute pancreatitis are associated with severe clinical syndromes, such as shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multiorgan failure, that influence some serum parameters, such as albumin, liver enzymes, and coagulation tests.

Plasma ionized calcium concentration may be low, and has been correlated with a poorer outcome.11

Serum amylase activity is of no clinical value in the clinical diagnosis of pancreatitis in cats; it actually decreases in experimental feline pancreatitis.13 However, the serum activity of both amylase and lipase may increase whenever glomerular filtration rate is reduced.

Serum lipase activity is modestly increased early in experimentally induced disease, but is frequently normal in cats with spontaneous pancreatitis. A recent study found a high level of agreement between the 1,2-o-dilauryl-rac-glycero-3-glutaric acid-(6′-methylresorufin) ester lipase assay and feline pancreas-specific lipase assay, suggesting that the method used for lipase measurement may influence sensitivity and specificity.14

Serum pancreatic lipase (Spec fPL, idexx.com) is the serum test that provides the most useful information to support, or exclude, a diagnosis of pancreatitis (see Feline Pancreatic Lipase Assays).

Feline Pancreatic Lipase Assays

The Spec fPL assay (idexx.com) is a commercially available monoclonal enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. A study presented in abstract form estimated the sensitivity and specificity of this test for diagnosing feline pancreatitis at 79% and 82%, respectively.15

Concentration results are considered:

- Diagnostic (positive) if ≥ 5.4 mcg/L

- A gray zone if > 3.5 mcg/L and < 5.4 mcg/L

- Negative if ≤ 3.5 mcg/L.

The Snap fPL (idexx.com) is a semiquantitative point-of-care test that can help rule out pancreatitis. A value of > 3.5 mcg/L is considered positive; therefore, a positive result must be confirmed by a Spec fPL assay.

With both tests, positive results must be interpreted in light of other clinical information, rather than considered an endpoint of diagnostic evaluation. After an episode of pancreatitis, the duration of fPL increase has not been reported.

Asymptomatic cats with persistently increased fPL concentrations may be encountered, especially if the fPL is included as a routine test in geriatric health panels. This may correlate with histologic evidence of pancreatitis reported in cats lacking clinical signs of disease.1

Abdominal Radiography

Exclusion of other causes of vague gastrointestinal signs, such as partial intestinal obstruction, is a major rationale for survey abdominal radiography in cats with clinical signs compatible with pancreatitis. Thoracic radiographs may detect pleural fluid or pulmonary edema, both of which have been associated with acute pancreatitis and other complications, such as pneumonia.

Abdominal Ultrasonography

Abdominal ultrasonography is a key diagnostic test in cats suspected of having pancreatitis; Table 2 lists the most important ultrasound findings.

| TABLE 2 Important Ultrasound Findings in Cats with Pancreatitis14,16-17 |

| · Increased echogenicity of mesenteric fat immediatel surrounding the pancreas*

· Increased pancreatic thickness (enlarged pancreas) · Irregular pancreatic margins · Peripancreatic free fluid · Hypoechoic, hyperechoic, or mixed-echoic pancreas · Mass effect in cranial abdomen · Dilated common bile duct |

The reported sensitivity of abdominal ultrasound for detecting feline pancreatitis varies widely (11%— 68%),16 even when performed by board-certified radiologists. Therefore, some cats with biopsy-confirmed acute pancreatitis have no detectable sonographic abnormalities. However, the sensitivity of ultrasonography increases with increasing severity of pancreatitis.18

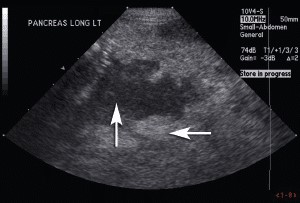

Abnormal sonographic findings are highly specific for pancreatitis—a cat with compatible clinical signs and visible changes in the pancreas is very likely to be correctly diagnosed with pancreatitis (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Sagital sonographic image of the left limb of the pancreas in an 8-year-old neutered male Maine Coon cat. The cat presented with diabetic ketoacidosis (new diagnosis), evidence of abdominal pain, and a palpable midcranial abdominal mass. The pancreas is enlarged and hypoechoic (up arrow) with irregular margins. The mesentery adjacent to the pancreas (horizontal arrow) is hyperechoic (reactive). These changes are consistent with pancreatitis. Courtesy Dr. Kari Anderson, University of Minnesota Veterinary Medical Center

Fine-Needle Aspiration

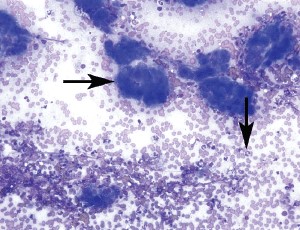

Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspirates of the pancreas and/or peripancreatic tissue may assist in the diagnosis of pancreatitis (Figure 3), and may also be helpful when nodular changes are present.

FIGURE 3. Pancreatic aspirate from a cat with pancreatitis (200×, Wright’s-Giemsa stain). There are multiple cohesive clusters of slightly hyperplastic pancreatic exocrine cells characterized by increased cytoplasmic basophilia (horizontal arrow). The background contains blood and increased numbers of neutrophils (vertical arrow) with occasional foamy macrophages. Courtesy of Dr. Leslie Sharkey, University of Minnesota Veterinary Medical Center

INITIAL THERAPY

The initial medical management of cats with acute pancreatitis must not be delayed until a diagnosis is confirmed. In experimental studies, a major factor in the progression of mild pancreatitis to severe pancreatitis is disturbed pancreatic microcirculation.

Early IV fluid therapy with a balanced, isotonic replacement crystalloid (eg, lactated Ringer’s solution, 0.9% saline, Plasma-Lyte 156, Normosol-R), supplemented with potassium and glucose as necessary, is recommended. This emphasis on early fluid resuscitation is consistent with human treatment guidelines for acute pancreatitis and is of critical importance.19

Potassium supplementation (up to 20—30 mEq potassium chloride/L of fluids) is necessary to replace losses and address reduced intake, and should be monitored by serial measurement of serum potassium levels. The level of supplementation may need to be reduced in patients with mild clinical signs, or increased in patients with concurrent diabetic ketoacidosis.

Calcium gluconate (50—150 mg/kg IV as a slow bolus) may be required for symptomatic hypocalcemia (tremors, seizure activity), a possible complication of acute pancreatitis, and serum ionized calcium concentrations should be monitored regularly during calcium therapy. Begin with a portion of this dose, and discontinue if ionized calcium normalizes. Continuous low-dose IV infusions of calcium gluconate (5—10 mg/kg/H IV) are required by some cats.

Insulin therapy is initiated in diabetic patients.5

Colloids, such as hydroxyethyl starch, are useful when hypoproteinemia is present, and may have antithrombotic effects that help maintain microcirculation. However, use of synthetic colloids in companion animals is increasingly being debated due to adverse effects on renal function noted in human patients.20

Plasma transfusion theoretically provides a source of circulating protease inhibitors, but numerous human studies fail to support its use, and 1 retrospective canine pancreatitis study failed to demonstrate a benefit.

MEDICAL THERAPY

Antiemetics

Nausea and vomiting may be severe in patients with acute pancreatitis.

- The potent antiemetic maropitant, an NK1 receptor antagonist, is useful for controlling emesis (and probably nausea) and providing visceral analgesia.21

- An alternative antiemetic is a 5-HT3 antagonist (ondansetron or dolasetron), which may be combined with maropitant in severe cases.

- The dopaminergic antagonist metoclopramide may help enhance motility in the upper gastrointestinal tract. It acts as a weak peripherally acting antiemetic in dogs, but this effect is questionable in cats.

- The histamine-2 receptor antagonist ranitidine may be selected for dual acid inhibition and prokinetic effects. Correction of hypokalemia also helps improve gastrointestinal motility.

Gastroprotectants

Gastric acid suppression is commonly incorporated into therapy for feline acute pancreatitis. The rationale includes protecting:

- The esophagus from exposure to gastric acid during episodes of vomiting

- Against gastric ulceration, to which patients with pancreatitis may be predisposed due to hypovolemia and local peritonitis.

Higher gastric pH may decrease exocrine pancreatic stimulation but remains undocumented as a treatment for pancreatitis.

When gastric acid suppression is desired, a proton-pump inhibitor (pantoprazole) may be preferred over a histamine-2 receptor antagonist; an experimental study in rats demonstrated that pantoprazole reduced inflammatory changes and leakage of pancreatic acinar cells.22

When a histamine-2 receptor antagonist is used, famotidine is believed to be most effective for suppression of gastric acid production.

Analgesics

Pain management is a critical aspect of treating acute pancreatitis, and can be easily overlooked because cats may not exhibit easily recognized signs of pain. Analgesia can be provided using opioids, such as buprenorphine or fentanyl, delivered by IV or SC injection, sublingual route, or transdermal patch.

Convincing evidence suggests that the antiemetic maropitant also provides visceral analgesia.21 Tramadol is usually avoided in cats because it can cause severe dysphoria.

Antibiotics

Acute pancreatitis is thought to begin as a sterile process, and reports of bacterial complications, such as pancreatic abscessation, are uncommon. Broad-spectrum antibiotics may be warranted in cats with complete blood count findings suggestive of sepsis but, otherwise, are not routinely used.

However, a recent study in cats using culture-independent methods9 suggested that bacterial infection may warrant greater consideration. Coliforms are the principal pathogens and are also seen in bile cultures from cats with cholangitis.23

Glucocorticoids

Historical reluctance to use corticosteroids for treating pancreatitis has been based on concern that these agents could lead to pancreatitis; however, no evidence supports this assumption in cats.

Corticosteroids exert broad anti-inflammatory effects, and may have a role in increasing production of pancreatitis-associated protein, which helps protect against inflammation. They may also address critical illness-related corticosteroid insufficiency, a relative adrenal insufficiency that could occur in acute pancreatitis.

Steroid use in cats with acute pancreatitis is being reconsidered but remains unexamined. There is no existing data supporting the use of corticosteroids in feline pancreatitis, and care must be exercised when considering their use in cats with diabetes. Judicious short-term corticosteroid administration may be considered in a cat with severe acute pancreatitis that is failing to respond to other therapies.