Bioguard Corporation

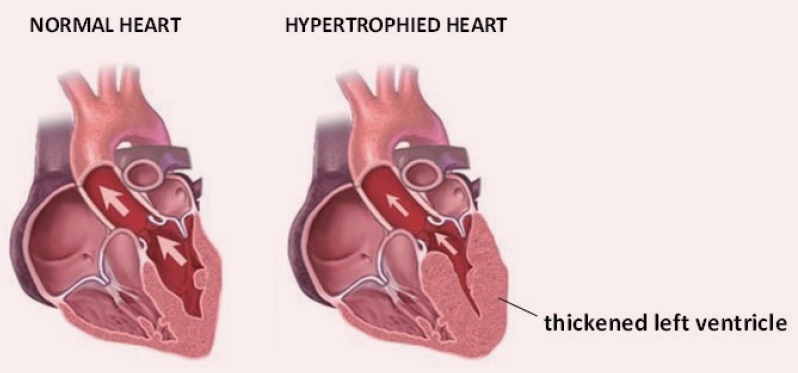

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a primary, familial, and hereditary heart condition, and it is the most common heart disease in cats. Its key characteristic is primary concentric left ventricular hypertrophy (thickening of the heart wall), which occurs without pressure overload (such as from aortic stenosis), hormone stimulation (like in hyperthyroidism or acromegaly), myocardial involvement (such as from lymphoma), or other non-cardiac diseases.

The heart consists of four chambers: the left atrium and ventricle, and the right atrium and ventricle. The right side of the heart pumps deoxygenated blood to the lungs, while the left side pumps oxygenated blood to the rest of the body.

In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), some cardiomyocytes are unable to function properly, causing the normal ones to enlarge in an attempt to maintain the heart’s output. However, this excessive thickening of the myocardium leads to a thickened left ventricle that encroaches on the ventricular space. As a result, the ventricle’s capacity to hold a normal amount of blood is reduced, and the myocardium becomes stiffer with decreased contractility.

This alters the pressure within the left side of the heart, eventually causing the left atrium to enlarge. An enlarged left atrium increases the risk of congestive heart failure (CHF) in cats, which is marked by fluid accumulation in the lungs (pulmonary edema) or around the lungs (pleural effusion).

HCM can occur at any age, but it is most common in adult cats around six years or older. Breeds such as Maine Coon, Ragdoll, and Domestic Shorthair are most frequently affected, while Persian, British Shorthair, and American Shorthair cats are also at higher risk.

The exact cause of HCM in cats is not fully understood. Research suggests that mutations in the myosin binding protein C gene (MYBPC3) are linked to HCM in Maine Coon and Ragdoll cats. Specifically, the mutations A31P and R820W in the MYBPC3 gene are associated with this condition in these two breeds.

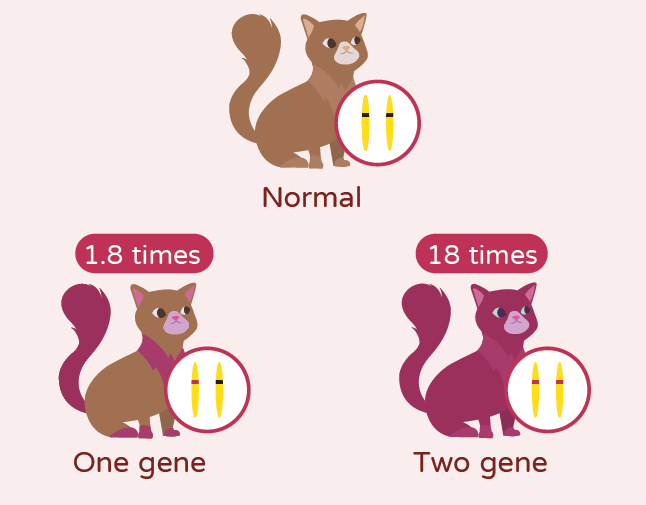

The MYBPC3 mutation exhibits incomplete penetrance, meaning it is not a purely dominant trait. Cats with one copy of the mutated gene have a relative risk of HCM that is about 1.8 times higher than normal cats. However, cats with two copies of the mutation have a significantly higher relative risk, about 18 times greater. Despite this, some Maine Coon cats without the MYBPC3 mutation have also been diagnosed with HCM. In studies, the incidence of HCM in cats without the original mutant gene was approximately 5.4%. This indicates that while the MYBPC3 mutation is a significant factor, it is not the sole cause of HCM in Maine Coon cats, and other contributing factors remain unclear.

Clinical Symptoms

Most cats with HCM show no clinical symptoms, especially those with mild to moderate disease, making early detection challenging. Even severely affected cats may initially be asymptomatic but typically progress to left heart failure, systemic thromboembolism, or sudden death. Cats with heart failure exhibit signs such as shortness of breath and dyspnea due to pulmonary edema or pleural effusion. Systemic thromboembolism commonly presents as hind limb paresis or paralysis, accompanied by acute pain, lack of pulse, and fever.

Genetic Testing

This test is recommended for purebred cats with a genetic predisposition, especially Maine Coon and Ragdoll breeds.