Pigeon Circovirus

Bioguard Corporation Pigeon circovirus (PiCV) is an infectious disease that mainly affects young pigeons between 1 and 4 months of age. Mortality is variable, but it can approach 100%. Pigeon circovirus infections have led to the loss of lymphoid tissue in immune system organs, and for this reason, PiCV is regarded as an immunosuppressive agent […]

Lyme Disease in Dogs

Oliver Organista, LA Lyme disease is triggered by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which belongs to the spirochete class, characterized by its worm-like, spiral shape within the genus Borrelia. This bacterium is spread to both dogs and humans through the bite of an infected black legged tick, also known as the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis). The […]

Pancreatitis in Dogs

Dr. Sushant Sadotra Canine Pancreatitis is one of the most common endocrine diseases occurring in dogs. However, it is more prevalent in dog breeds such as Miniature Schnauzers, Yorkshire Terriers, Cocker Spaniels, Dachshunds, Poodles, and sled dogs. Pancreatitis, a severe inflammatory condition of the pancreas, can be short-term or long-term, based on the level of […]

Kidney Diseases in Cats

Lloyd Alexandria Chavez, R.M.T Cats possess a pair of kidneys located on either side of their abdomen, playing a crucial role in eliminating waste from their system. These organs are also key in regulating the balance of fluids, minerals, and electrolytes in the body, conserving water and protein, and supporting blood pressure and the […]

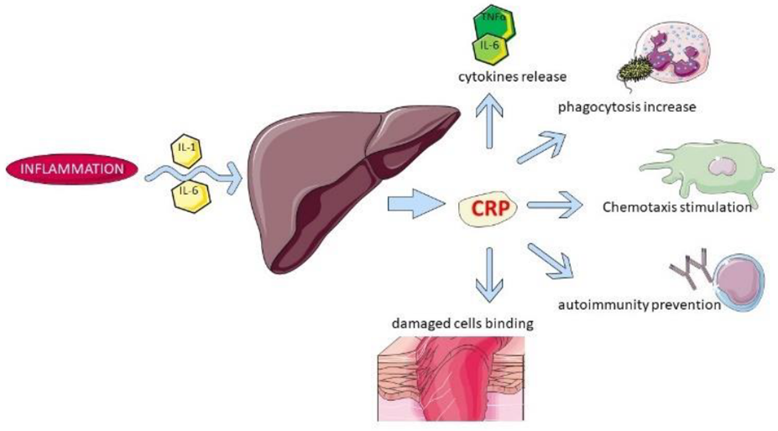

C-Reactive Protein

Sushant Sadotra The acute phase response (APR) is the early typical systemic response prompted by homeostasis disturbances such as injuries, infection, neoplasia, and other pathologies. Acute phase proteins get released from the liver into the blood after such stimulations. Therefore, elevated levels of such proteins can be used to indicate systemic inflammation. C-reactive protein, also […]

Rabbit Hemorrhagic Disease

Long Pham Introduction Rabbit hemorrhagic disease (RHD) is a highly contagious and lethal viral disease caused by a virus from the Caliciviridae family. This disease seems to only affect European rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus),both domesticated and wild rabbits. However, a newer strain of the virus, RHDV2, can affect rabbits with previous immunity to RHD and also […]

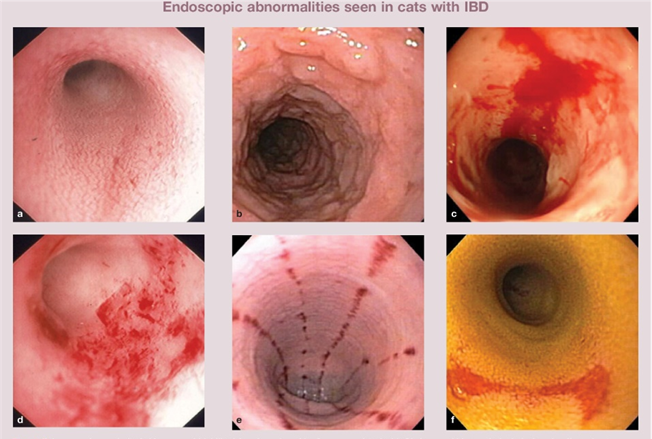

Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Cats

Sushant Sadotra Feline inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic condition that affects a cat’s gastrointestinal (GI) tract. The walls of the GI tract become thickened due to the infiltration of inflammatory cells, disrupting the cat’s ability to digest and absorb food properly. Although IBD can affect cats of any age, middle-aged and older cats […]

Canine Chronic Hepatitis

Chavezlloyd Alexandria Baldago Chronic hepatitis is a condition in dogs that may occur due to various disease processes. It indicates a previous occurrence of inflammation and possibly cell death in the liver. The inflammation is caused by the infiltration of different types of white blood cells that are involved in the immune system. Necrosis, which […]

Respiratory Tract Disease Complex in Cats

Sushant Sadotra, PhD/Diagnostic specialist Feline respiratory disease (FRD) syndrome or feline upper respiratory tract disease complex is a common infection in cats caused mainly by Feline Herpesvirus (FHV-1), Feline Calicivirus (FCV), Chlamydophila felis, Mycoplasma spp., and Bordetella bronchiseptica. About 90% of all upper respiratory infections are caused by FHV-1 and FCV. Common Symptoms: · Sneezing · Nasal […]